In the rapidly evolving field of additive manufacturing, understanding material properties is essential for producing reliable and functional parts. Among these properties, ductility plays a critical role in determining how a 3D printed component behaves under mechanical stress. While strength and stiffness often dominate discussions, ductility is equally important because it governs how a material deforms before fracture.

What is Ductility?

Ductility is the ability of a material to undergo significant plastic deformation before rupture. In simpler terms, it describes how much a material can stretch, bend, or elongate without breaking.

• Measurement: Ductility is commonly quantified by elongation at break in tensile testing, expressed as a percentage of the original gauge length. For example, a material with 50% elongation can stretch to half its original length again before failure.

• Microstructural Basis: Ductility arises from the ability of atoms to slip past one another along crystallographic planes. Materials with more mobile dislocations, such as metals, tend to be highly ductile. Brittle materials, like ceramics, lack this mobility and fracture suddenly.

• Everyday Examples: Copper wires are ductile as they can be drawn into thin strands without breaking. Glass, on the other hand, is brittle as it fractures with little warning.

In engineering contexts, ductility is a safeguard against catastrophic failure. A ductile material provides warning signs (visible deformation) before breaking, whereas brittle materials fail abruptly.

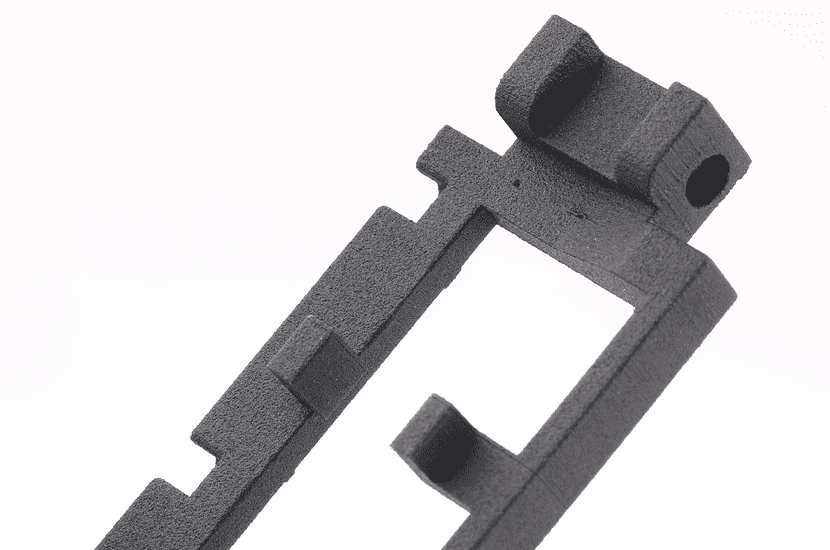

Image Copyright © 3DSPRO Limited. All rights reserved.

Ductility’s Impact on 3D Printed Parts

When applied to 3D printing, ductility determines how printed parts perform under mechanical loads, thermal cycling, and real-world stresses.

Key Impacts:

• Failure Mode: Ductile parts deform gradually, allowing users to detect impending failure. Brittle parts fracture suddenly, which can be dangerous in load-bearing applications.

• Durability: Higher ductility improves fatigue resistance, as the material can absorb cyclic stresses without cracking.

• Design Flexibility: Ductile materials enable thinner walls, snap-fit joints, and complex geometries that rely on controlled deformation.

• Safety Margin: In critical applications such as aerospace or medical devices, ductility provides a margin of safety by preventing catastrophic breakage.

Example:

Consider a 3D printed clip designed to flex repeatedly. If printed in PLA (low ductility), the clip may crack after a few cycles. If printed in Nylon (high ductility), it can withstand repeated bending without failure.

Thus, ductility directly influences whether a design is practical, reliable, and safe.

Ductility of 3D Printed Polymers vs Metals vs Composites

Different material classes used in additive manufacturing exhibit varying levels of ductility. Understanding these differences is crucial for material selection.

Polymers

• PLA (Polylactic Acid): Low ductility. PLA is stiff and brittle, prone to cracking under stress.

• ABS (Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene): Moderate ductility. More impact-resistant than PLA, suitable for functional parts.

• PETG (Polyethylene Terephthalate Glycol): Good ductility. Balances strength and flexibility, often used for mechanical components.

• Nylon (Polyamide): High ductility. Excellent elongation at break, making it ideal for flexible and durable parts.

Metals

• Aluminum Alloys: Moderate ductility. Useful for lightweight structural components, but can be sensitive to porosity in prints.

• Titanium Alloys: Good ductility combined with high strength. Widely used in aerospace and medical implants.

• Stainless Steel: High ductility. Resistant to fracture, suitable for load-bearing applications.

Composites

• Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Polymers: Reduced ductility due to brittle fibers. High stiffness but prone to sudden fracture.

• Glass-Fiber Composites: Similar to carbon fiber, with improved toughness but limited ductility.

• Hybrid Composites: Balance between ductility of matrix and brittleness of reinforcement.

Strategies to Improve Ductility in 3D Prints

While ductility is largely material-dependent, engineers can employ several strategies to enhance ductility in printed parts.

1. Material Selection

• Choose inherently ductile materials such as Nylon, PETG, or ductile metals.

• Avoid brittle materials like PLA for applications requiring flexibility.

2. Printing Parameters

• Temperature: Higher extrusion temperatures improve layer adhesion, reducing brittleness.

• Infill Density: Lower infill allows more deformation, increasing ductility.

• Layer Orientation: Printing with layers aligned to stress direction enhances ductility.

3. Post-Processing

• Annealing: Controlled heating can relieve internal stresses and improve ductility.

• Blending: Mixing polymers (e.g., ABS with TPU) can improve ductility.

• Reinforcement: Adding ductile fillers or fibers can balance stiffness and ductility.

4. Design Considerations

• Incorporate fillets and rounded corners to reduce stress concentrations.

• Avoid sharp transitions that promote brittle fracture.

• Use flexible geometries (e.g., living hinges) where ductility is critical.

Differences between Ductility and Toughness

Ductility is often confused with toughness, but they are distinct properties.

• Ductility: Ability to deform plastically before fracture. Measured by elongation at break.

• Toughness: Ability to absorb energy before fracture. Measured by the area under the stress-strain curve.

Key Differences:

• A material can be ductile but not tough (e.g., soft metals that deform easily but absorb little energy).

• A material can be tough but not ductile (e.g., certain composites that resist fracture but deform minimally).

• Engineering Implication: Ductility ensures gradual failure, while toughness ensures resistance to impact and energy absorption.

Example:

• Rubber: Highly ductile and tough; it stretches and absorbs energy.

• Glass: Neither ductile nor tough; it fractures suddenly.

• Carbon Fiber Composite: Tough but not ductile; it resists impact but fails abruptly when overloaded.