Over the last decade construction-scale 3D printing has evolved from experimental prototypes to commercial pilots and small production runs, driven by advances in robotic platforms, printable materials, and digital design workflows. Practitioners are already using printing to speed delivery, cut material waste, and unlock complex geometries that are hard or expensive with conventional methods.

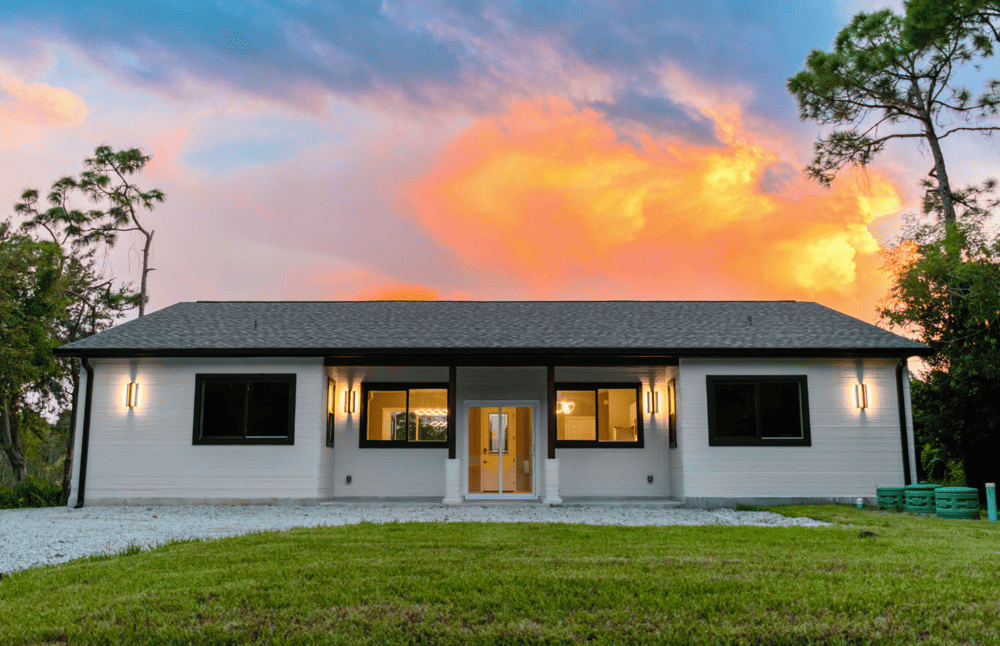

Image Source: Apis Cor

What is Construction-Scale 3D Printing?

Construction-scale 3D printing means using additive manufacturing methods to produce building elements or whole structures at architectural scales. It covers a range of approaches from printing small decorative elements and facade panels offsite to large gantry or robotic systems that extrude printable concrete or cementitious mixes layer-by-layer on site. Two broad styles are common:

• Off-site prefabrication: printed components (facade panels, molds, bespoke cladding) are manufactured in a factory and then transported to site.

• On-site printing: large printers (gantries, robotic arms, or mobile rigs) deposit material directly where the element or building will stand, reducing transport and enabling rapid enclosure construction.

These methods are distinguished from traditional 3D printing by scale, structural performance requirements, and the need to integrate with building systems, code requirements, and on-site logistics. Recent reviews and industry reports emphasize that construction printing is best viewed as an integrated digital-to-physical workflow (BIM → slicing → printing → QA) rather than a single machine doing all the work.

3D Printing Technologies Used in Architecture and Construction

Several families of printing technology are used in construction. Here are the most important ones and when each is used.

1. Extrusion of Cementitious Mixes (Concrete Printing)

The most common large-scale approach is extrusion: a mortar or concrete mix is pumped to a nozzle and deposited in layers along a programmed path. Gantry systems and robotic arms are both used for this. It is suitable for load-bearing walls, partitions, and structural components when combined with appropriate reinforcement strategies. Many commercial deployments use this approach.

2. Binder-Jetting and Sand-Casting Workflows

Binder-jetting can produce large molds or formwork by selectively binding particulate material (sand or similar) then using those molds for casting concrete or metal. It is well suited to complex bespoke components, ornate elements, or where a high-quality surface is needed.

3. Robotic composite layup and filament deposition

Robotic arms can lay continuous fiber composites or extrude polymer/filament materials to form facades, panels, and lightweight structural elements. These processes are attractive where high strength-to-weight and tailored anisotropy are important.

4. Hybrid Systems (Printing + Reinforcement Placement / CNC)

Real projects frequently mix processes: printing wall geometry, then inserting reinforcement cages, adding conventional concrete pours for lintels, or using CNC finishing for precise interfaces. Hybridization helps bridge performance and code gaps.

Notable firms and platforms in the field include ICON (large-format onsite printing for housing projects) and COBOD (gantry printers used for residential and multi-unit work), which show how different machine formats are being applied in real construction projects.

Materials for Construction-Scale Printing

Material science is central to construction printing. Common material classes:

• Printable Concrete and Cementitious Mortars: mixes are engineered for pumpability, buildability (supporting subsequent layers), fast set or controlled open time, and reduced shrinkage. Admixtures (retarders, accelerators, thickeners) and particle packing strategies are routinely used.

• Geopolymers and Low-Carbon Binders: alternatives to Portland cement that can lower embodied carbon and sometimes provide better print rheology; they are an active research area for structural applications.

• Fiber Reinforcement and Mesh Strategies: because layerwise extrusion can create anisotropy and weak interfaces, fiber-reinforced mixes, embedded meshes, or post-tensioning are used to meet structural requirements.

• Polymers and Composites: used primarily for facades, lightweight panels, and non-structural bespoke elements.

• Specialist Ceramics and Metals: currently limited to smaller components, tooling, or inserts rather than monolithic walls.

Durability, curing behavior, freeze–thaw performance, and long-term testing remain necessary before many printed materials are accepted broadly in codes and by insurers.

Pros and Cons

|

Pros |

Cons |

|

Design freedom: complex, organic, and optimized geometries (lattices, variable thickness) that reduce parts and allow functional integration. |

Regulatory uncertainty and code compliance: many jurisdictions lack clear pathways for certifying printed structural elements; permitting and insurer acceptance remain hurdles. |

|

Speed and labor reduction: printing walls or modules can be faster and require fewer onsite workers for repetitive tasks. |

Structural variability and reinforcement challenges: layer interfaces and load paths need careful engineering; traditional reinforcing methods are not always straightforward to combine with printing. |

|

Material efficiency and waste reduction: additive processes can reduce formwork and cutting waste compared with conventional methods. |

Finish quality and tolerances: printed surfaces often require post-processing to meet architectural finish standards. |

|

Local and on-demand production: potential for localized supply chains and rapid response housing/relief shelters. |

Logistics and robustness: large printers and the required material handling raise site-access, power, and weather challenges. |

|

/ |

Workforce and digital skills gap: successful projects need teams competent in digital design, material science, and on-site robotics. |

Applications

• Affordable and Emergency Housing: fast walls and modules for quick, low-cost shelter prototypes; companies like ICON have run multiple pilot housing projects.

• Bespoke Facades and Complex Envelopes: lightweight, highly detailed panels that would be costly with conventional molding.

• Infrastructure Components: small bridges, culverts, and precast elements where customization and reduced lead time matter.

• Formwork and Tooling: printed molds for casting complex parts reduce time and material used in traditional formwork.

• High-Value Architectural Statements: sculptural installations, pavilions, and demonstration buildings that spotlight the aesthetic potential of additive techniques. Evidence of multi-story printed constructions has already appeared in the field, demonstrating the technology’s growing maturity.

COMMENTS

- Be the first to share your thoughts!