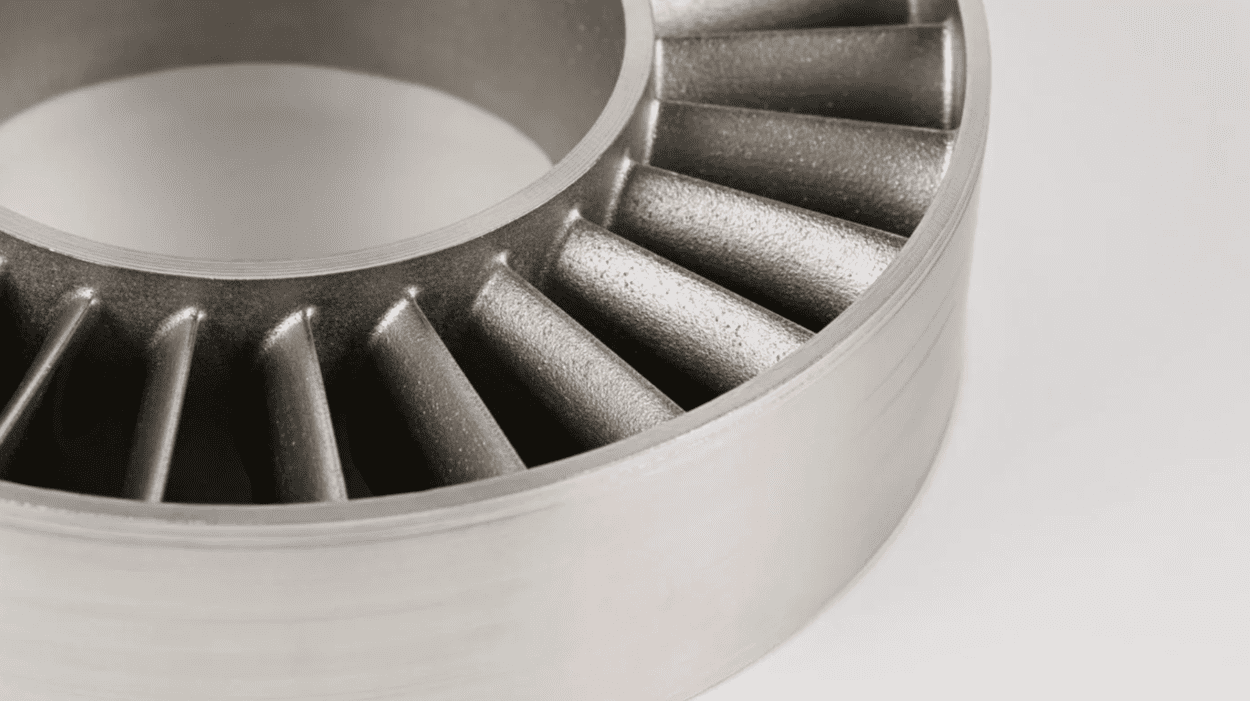

Cobalt-chrome (CoCr) alloys have become a mainstay in high-performance additive manufacturing where strength, wear resistance, and high-temperature stability are required. Originally important in dental and orthopedic implants, CoCr is now widely used in aerospace for components exposed to heat, abrasion, or cyclic loading.

Image Source: EOS

Cobalt-Chrome Alloys

Cobalt-Chrome refers to a family of cobalt-based alloys alloyed principally with chromium and often with additions such as molybdenum, tungsten, or nickel to tailor strength, corrosion resistance, and wear performance.

Mechanical Properties of Cobalt-Chrome

• High strength and hardness. CoCr alloys deliver excellent static strength and retain mechanical properties at elevated temperatures, making them suitable for hot-section and wear-critical applications.

• Wear and corrosion resistance. Chromium provides a stable, protective oxide, while other alloying elements increase resistance to frictional wear and chemical attack.

• Biocompatibility. Certain CoCr grades are accepted for medical implants due to low ion release and good tissue compatibility when finished properly.

• Thermal stability. CoCr maintains strength at temperatures that would soften many stainless steels, although it is heavier (higher density) than titanium alloys.

• Tradeoffs. Compared with titanium, CoCr is denser and usually heavier for the same volume; compared with stainless steels, it offers better wear resistance and high-temperature strength but can be more challenging to machine and finish.

3D Printing Processes Used for CoCr

Powder Bed Fusion (PBF/SLM)

Selective laser melting (SLM) or laser powder bed fusion (LPBF) is the most common method for CoCr. A laser selectively melts thin layers of gas-atomized powder to build the part.

Advantages:

• High resolution and good surface finish for complex geometries.

• Well-developed process windows for common CoCr grades.

Challenges:

• Residual stress and distortion must be managed.

• Powder handling, recycling strategy, and oxygen control are critical.

Directed Energy Deposition (DED)

DED deposits and melts wire or powder onto a substrate using a focused energy source (laser, electron beam, or plasma).

Best for:

• Repairs or adding features to existing components.

• Large parts where the PBF build volume is limiting.

Tradeoffs: coarser microstructure and generally lower surface fidelity than PBF.

Binder Jetting + Sintering

Binder jetting prints a green part from powder and binder, then the part is sintered and densified (often with HIP). Advantages include higher build speed and potentially lower cost for some geometries; challenges include achieving full density and controlling shrinkage during sintering.

Engineering Considerations

Design for AM (DfAM)

• Support strategy: CoCr parts often need supports for overhangs to control distortion, but supports add post-processing effort. Orient parts to minimize critical supports.

• Lattice/porous structures: For medical implants, controllable porous architectures encourage bone ingrowth; for aerospace, lattices enable stiffness tailoring and weight savings.

Thermal Stresses and Distortion

Rapid melting and solidification induce residual stresses. Mitigation techniques include build orientation optimization, preheating the build plate, optimized support placement, and controlled scan strategies.

Post-processing and Heat Treatment

• Hot Isostatic Pressing (HIP): Reduces internal porosity, increases fatigue life and ductility.

• Solution annealing and aging: Tailor microstructure and mechanical properties.

• Machining and polishing: Necessary for tight tolerances and to achieve the required surface roughness, especially in medical devices where surface topography affects biocompatibility.

• Surface treatments: Coatings, electropolishing, and passivation can reduce wear and corrosion or improve osseointegration for implants.

Aerospace Applications

In aerospace, CoCr is chosen where wear resistance, fatigue performance, and thermal stability outweigh its higher density compared to titanium, such as:

1. Wear-critical components: valve seats, bearings, and seals exposed to abrasive or erosive environments.

2. Hot-section hardware: elements near turbines where temperature and oxidation resistance are needed.

3. Part consolidation: complex assemblies (multiple brazed or bolted parts) can be consolidated into a single printed component, reducing assembly steps and potential leak paths.

4. Repair: DED is often used to repair high-value components made from CoCr or to add localized material to worn faces.

Medical and Dental Applications

CoCr has a long history in the medical field; 3D printing has broadened what’s possible.

Orthopedic and Dental Uses

1. Orthopedic implants: components such as femoral heads, joint resurfacing implants, and modular implant components benefit from CoCr’s wear resistance and stiffness.

2. Dental frameworks: removable partial denture frameworks and implant-retained prosthetics take advantage of CoCr’s strength and form stability.

3. Patient-specific implants and instruments: AM enables custom geometries matched to patient anatomy and surgical guides.

Surface Design for Biology

Porous structures and controlled surface roughness promote bone ongrowth and ingrowth. Designers can create gradients of porosity, such as solid internal cores with porous exterior regions, to balance strength and biological integration.

Biocompatibility and Sterilization

When processed and finished correctly, many CoCr grades meet medical biocompatibility expectations. Sterilization compatibility and corrosion resistance in physiological environments must be validated for each design and finish. Medical manufacturers must follow regulatory guidance and clinical testing requirements in their target markets.

COMMENTS

- Be the first to share your thoughts!