What is Ceramic Casting?

At its simplest, ceramic casting is a process where a liquid or semi-liquid ceramic formulation is introduced into a shaped cavity (the mold) and then solidified into the desired geometry. The solidification can occur by drying (water removal), chemical gelling, binder burnout and sintering, or freezing/solidification, depending on the method.

Two connected but distinct uses of the term are important to keep apart:

• Casting to make ceramic parts. Examples: slip casting pottery, pressure casting sanitaryware, or injection molding of ceramic feedstock to make dense technical ceramic components.

• Using ceramics as molds. Example: producing a ceramic shell around a wax pattern, then pouring metal into the shell, common in jewelry and aerospace (investment casting).

Both families share common concerns, such as mold design, shrinkage, surface finish, and thermal processing, but their materials and end goals differ.

Image Source: Lithoz

Core Concepts You Need to Know

• Slip: A liquid suspension of ceramic powder in water. Slip rheology is crucial to getting consistent castings.

• Green Body: The shaped but unfired ceramic object. It’s fragile and contains bound water or binders.

• Leather-Hard / Bone-Dry: Stages of drying; leather-hard is stiff enough to trim, bone-dry means all free water is gone.

• Bisque Firing / Sintering / Vitrification: Heat treatments that remove binders, burn out organics, bond particles, and densify the piece. Sintering is used for technical ceramics to reach high density.

• Shrinkage: Most ceramic bodies shrink during drying and firing. Typical shrinkage varies by formulation and must be designed into molds.

• Mold Types: Absorbent plaster (for slip), flexible silicone, metal (for injection or pressure casting), and ceramic shell (for investment casting).

• Defects Linked to Processing: Cracks, warpage, pinholes, and delamination generally stem from poor drying, inadequate formulations, or mold design.

Ceramic Casting Methods

Slip Casting

• How it works: Pour slip into an absorbent plaster mold. The plaster draws water from the slip, forming a solid layer (the shell) against mold walls. When the shell is the right thickness, pour out the remaining slip and allow the shell to stiffen.

• Good for: Hollow objects such as teapots, vases, and sanitaryware.

• Pros/cons: Excellent surface finish and detail; limited to relatively simple internal features and requires time for shell growth and drying.

Pressure and Centrifugal Casting

• How it works: Apply pressure or rotation to force slip into finer details and speed shell formation.

• Good for: High-volume tableware and sanitaryware with tighter porosity control.

• Pros/cons: Faster, denser parts than standard slip casting, but needs specialized equipment.

Tape Casting

• How it works: A ceramic slurry is spread into thin sheets and dried; used for electronic substrates and thin components.

• Good for: Flat, thin components like multilayer ceramic substrates.

Ceramic Injection Molding (CIM)

• How it works: Ceramic powder is mixed with polymer binders to form a feedstock that is injection-molded like plastic. Parts are debound and sintered.

• Good for: Complex geometries and higher-volume production of small parts.

• Pros/cons: High precision and throughput; requires debinding and sintering infrastructure.

Gelcasting

• How it works: A monomer is added to a ceramic slurry; after molding, the monomer polymerizes, producing a rigid green body with excellent mechanical strength.

• Good for: High-performance ceramics and complex shapes that need strong green-state handling.

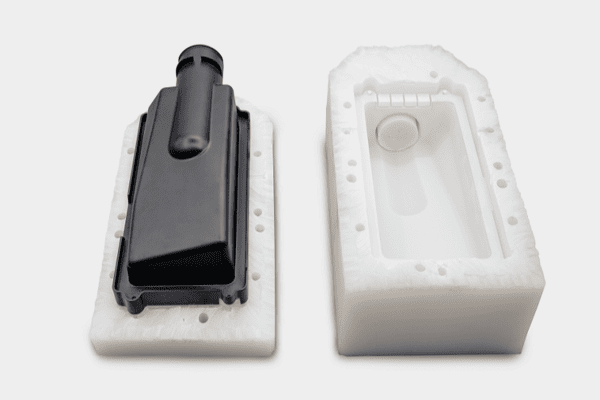

Ceramic Shell / Investment Casting

• How it works: Create a sacrificial pattern (usually wax), coat it repeatedly with ceramic slurry and refractory layers to build a shell, burn out the wax, and pour molten metal into the ceramic mold. The ceramic shell is removed after cooling.

• Good for: Precision metal parts such as turbine blades, jewelry, and complex castings requiring a good surface finish.

• Pros/cons: Outstanding surface detail and thin-wall capability; time-consuming multilayer process.

Work Flow for a Typical Slip-Cast Ceramic Piece

1. Prepare the Slip

Mix ceramic powder (clay body or porcelain) with water and additives (deflocculants, binders). De-air the slip (vacuum or settling) to remove bubbles.

2. Prepare the Mold

Clean plaster mold, apply release (if needed), and assemble multi-part molds. Warm the mold slightly to control shell growth if required.

3. Casting

Pour the slip into the mold and let it sit. Water is absorbed, and a shell forms. Monitor shell thickness by time or small samples.

4. Drain and Allow to Stiffen

Pour out excess slip when the desired thickness is reached. Let the part set until leather-hard.

5. Demold and Trim

Carefully remove the green body, trim seams, and join pieces (e.g., handles) when still leather-hard.

6. Drying

Even, controlled drying to bone-dry. Avoid drafts and rapid temperature swings.

7. Bisque Firing

First firing to remove chemically bound water and organic additives, and to strengthen the piece for glazing.

8. Glazing (optional)

Apply glaze and clean off areas that must remain unglazed (e.g., kiln shelf contact points).

9. Glaze Firing / Sintering

Final firing that vitrifies the body and melts the glaze when used.

10. Post-processing

Sanding, piercing, or precision machining (for technical ceramics, additional grinding or lapping post-sintering may be needed).

Materials and Formulations

|

Category |

Typical Materials |

Typical Uses |

Common Casting Methods |

|

Earthenware |

Red clay, terracotta |

Decorative pottery, tiles |

Slip casting |

|

Stoneware |

Stoneware clay bodies |

Durable tableware, sinks |

Slip casting, pressure casting |

|

Porcelain |

Kaolin-based porcelain |

Fine ware, sanitaryware, art |

Slip casting, pressure casting |

|

Technical ceramics |

Alumina, zirconia |

Industrial parts, implants, wear parts |

Gelcasting, CIM, pressing + sinter |

|

Mold materials |

Plaster, silicone, ceramic shell |

Molds for ceramic or metal casting |

Plaster molds (slip), silicone molds, ceramic-shell investment |

Common Defects, Causes, and Fixes

1. Cracking

Caused by uneven drying, thick/thin sections, or trapped stresses.

Fix: even drying, redesign to avoid sudden thickness changes, add fillets and ribs.

2. Warping / Distortion

Uneven moisture or temperature gradients during drying/firing.

Fix: controlled drying, symmetric design, or support fixtures.

3. Pinholes / Blisters

Trapped air, organic contamination, or improper glazing.

Fix: degas slip, clean materials, adjust glaze fit.

4. Incomplete Fill / Thin Walls

Low slip solids or poor mold venting.

Fix: adjust slip rheology, add vents and appropriate mold design.

5. Delamination / Lamination

Layering due to poor slurry mixing or settling.

Fix: improve mixing, prevent settling, and use consistent casting procedures.

Applications

• Art and Tableware: Pottery, sculpture, porcelain dishes, and sanitaryware (toilets, sinks).

• Industrial Ceramics: Insulators, filters, wear parts, cutting tools, and biomedical implants made from alumina or zirconia.

• Electronics: Tape-cast substrates for multilayer ceramic capacitors or circuit carriers.

• Aerospace and Energy: Turbine blades, precision metal castings.

• Jewelry and Prototyping: Lost-wax + ceramic shell for fine detail.

FAQs

Q: What’s the difference between slip casting and ceramic-shell (investment) casting?

A: Slip casting forms the final ceramic object by de-watering slip in a plaster mold. Ceramic-shell casting uses a ceramic coating to make a mold around a wax (or other) pattern; the mold is used to cast metal or other materials.

Q: Why do ceramic parts shrink after firing?

A: Shrinkage occurs because particles pack closer during sintering as porosity is reduced and organic constituents burn out. Expect and design for predictable shrinkage (often 5–20%).

Q: Is ceramic casting suitable for mass production?

A: Yes. Injection molding, tape casting, and automated pressure casting are all mass-production methods. Traditional slip casting is slower but still used in high-volume industries (e.g., sanitaryware).

COMMENTS

- Be the first to share your thoughts!