Powder Lifecycle in MJF

Fresh Powder

New PA12 or other polymer powder arrives with a controlled particle size distribution, narrow morphology, stable surface chemistry, low moisture, and known thermal properties. Fusing and detailing agents, the liquids jetted by the printhead, are a core part of the process. They alter local absorption of infrared energy, define fused regions, and affect surface finish and interlayer bonding.

During A Build

The build cycle exposes powder to repeated short thermal cycles. Powder in the build bed experiences preheating to near the polymer’s melting or softening range. Particles in the fuse zone are melted and re-solidified. Neighboring carrier powder is heated but ideally remains unsintered. However, the thermal exposure can cause partial sintering of loose powder, formation of agglomerates, and surface chemistry changes where agents or gases interact with the polymer at elevated temperatures.

Collection and Handling

After the build, unsintered powder is sieved and collected from the bed and handling devices. Some fines are generated during the build and handling. Some powder agglomerates are broken by sieving, but not all. Many shops use a refresh strategy that mixes a percentage of unused powder with used powder to maintain consistent properties. Storage conditions and reconditioning steps further influence how the powder evolves between cycles.

End-of-Life

Eventually, powder reaches a point where reuse is no longer acceptable for quality-critical parts and is discarded, repurposed for low-performance applications, or reprocessed chemically.

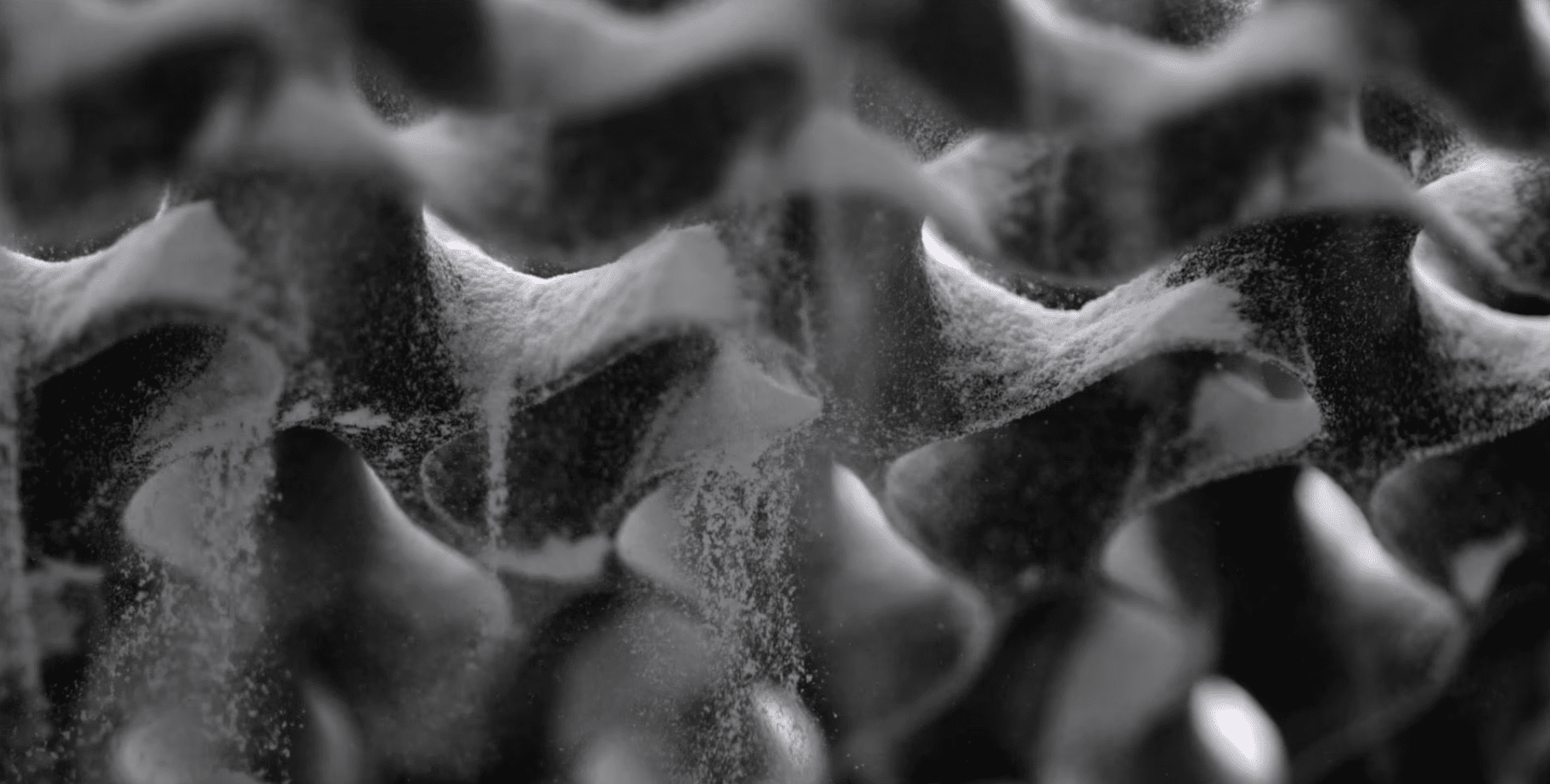

Image Source: HP

Key Powder Properties That Change with Reuse

Repeated thermal cycling and handling produce predictable changes in several powder characteristics. These property shifts are the link between reuse and part performance.

• Particle size distribution and fines generation: Each cycle tends to create more fines from mechanical handling and partial thermal degradation. Fines change how powder packs and flow, and dramatically increase interparticle cohesion.

• Bulk density and packing behavior: With more fines and agglomerates, bulk density can change, and the powder’s ability to pack uniformly under recoating reduces, which leads to layer-to-layer density variation.

• Flowability and Spreadability: Flowability metrics (Hall flow, shear tests) worsen as surface roughness from thermal damage and fines fraction increase. Poor flow leads to uneven layers, variable layer thickness, and occasional voids.

• Surface chemistry and contamination: Exposure to heat and fusing agents can cause surface oxidation, slight carbonization at the agent interface, or contamination by used fusing or detailing agent residues. Surface chemistry changes alter wetting by the fusing agent and interparticle fusion behavior during energy exposure.

• Molecular weight and thermal property shifts: Repeated exposure to elevated temperatures can produce chain scission or crosslinking, depending on chemistry and conditions. Typically, thermal aging decreases average molecular weight, which shifts the melt flow and glass transition.

• Morphology changes and agglomeration: Partial sintering can produce weakly bonded agglomerates that are difficult to completely re-break by sieving. Agglomerates pack poorly and create local density variation.

• Moisture uptake: If powder is stored improperly, absorbed moisture can cause hydrolytic degradation during subsequent heats and affect flowability and sintering.

How Altered Powder Properties Translate into Mechanical Changes

Increased Porosity and Lower Part Density → Reduced Strength and Stiffness

Poor packing and higher fines content lead to more trapped air and higher porosity after fusion. Porosity reduces load-bearing cross-section and acts as a stress concentrator, lowering tensile strength and effective Young’s modulus. Small increases in porosity (even a few percent by volume) can produce measurable drops in strength and stiffness.

Heterogeneous Layer Formation → Anisotropy and Variability

When recoated layers vary in density or contain agglomerates, mechanical properties become more orientation-dependent and less repeatable, which shows up as higher scatter in test results and increased difference between build orientations.

Reduced Molecular Weight → Lower Ductility and Toughness

Polymer chain scission reduces molecular weight, which commonly reduces elongation-at-break, impact resistance, and fracture toughness. Parts may feel “brittle” compared to those printed from virgin powder, even if nominal strength is similar.

Weakened Interparticle Bonding → Lower Fatigue Life and Interlaminar Strength

Surface contamination and depleted fusing agent performance can reduce effective bonding between particles and layers. Reduced interlayer adhesion lowers fatigue life, peel strength, and Z-direction mechanical properties more than planar properties.

Surface Defects and Inclusions → Reduced Fatigue and Fracture Initiation Sites

Fines, charred fragments, or unmelted agglomerates can act as initiation sites for cracks under cyclical or impact loading, sharply reducing fatigue resistance even when static tensile strength remains acceptable.

Altered Thermal Response → Inconsistent Fuse Behavior

If DSC/Tg/MFI change enough, the same energy input may produce different fusion extents. Under-fused zones have weak mechanical continuity; over-fused zones can embrittle the microstructure. Both worsen property uniformity and may reduce ultimate performance.

Net Effect on Common Mechanical Metrics

• Tensile strength: generally declines with high reuse and poor refreshing, primarily due to porosity and bonding loss.

• Young’s modulus: affected by density changes and anisotropy; often decreases but may be less sensitive than strength.

• Elongation at break: tends to drop noticeably with molecular weight loss and increased porosity, a key early indicator of degradation.

• Impact toughness and fatigue resistance: often the most sensitive; small surface defects and reduced adhesion cause large drops.

COMMENTS

- Be the first to share your thoughts!