The Engineering Reasons for Post‑Processing

LCD 3D printing, also known as masked stereolithography (MSLA), has become a cornerstone of resin‑based additive manufacturing. By projecting UV light through an LCD mask, entire layers of photopolymer resin are cured simultaneously, enabling high‑resolution prints with remarkable efficiency. Yet the raw output from an LCD printer is only half the story. Without post‑processing, parts remain chemically unstable, mechanically weak, and aesthetically unfinished. For engineers, post‑processing is a critical stage that defines the functional quality of the final component.

1. Material Science Perspective

Photopolymer resins undergo a chemical reaction when exposed to UV light, forming cross‑linked polymer chains. However, the curing process inside the printer is incomplete. Residual monomers and oligomers remain trapped within the part, leaving it tacky and mechanically inconsistent. Post‑processing ensures full polymerization, stabilizing the material and eliminating toxic residues. From a chemical engineering standpoint, this step transforms a semi‑cured object into a structurally reliable polymer component.

2. Mechanical Performance

Uncured resin parts exhibit reduced tensile strength, poor impact resistance, and dimensional instability. Engineers working with functional prototypes or load‑bearing components cannot rely on partially cured prints. UV post‑curing increases hardness, improves wear resistance, and enhances thermal stability. For example, a dental model must withstand repeated handling, while a mechanical prototype may undergo stress testing. Post‑processing ensures these parts meet performance requirements.

3. Dimensional Accuracy

During printing, supports and residual resin can distort fine geometries. Cleaning and curing stabilize dimensions, preventing warping or shrinkage. For applications requiring tight tolerances, such as snap‑fit assemblies or precision molds, post‑processing is the safeguard against dimensional drift.

4. Surface Integrity

Surface quality directly impacts usability and aesthetics. Residual resin leaves a sticky film, while support structures create scars. Post‑processing removes contaminants, smooths surfaces, and prepares parts for coatings or painting. In industries like jewelry or consumer products, surface finish is as critical as mechanical strength.

5. Safety Considerations

Uncured resin is chemically active and potentially hazardous. Direct skin contact can irritate, and inhalation of fumes poses risks. Post‑processing eliminates these hazards by fully curing the resin and removing residues. For biocompatible applications, such as dental or medical models, safety is on top priority.

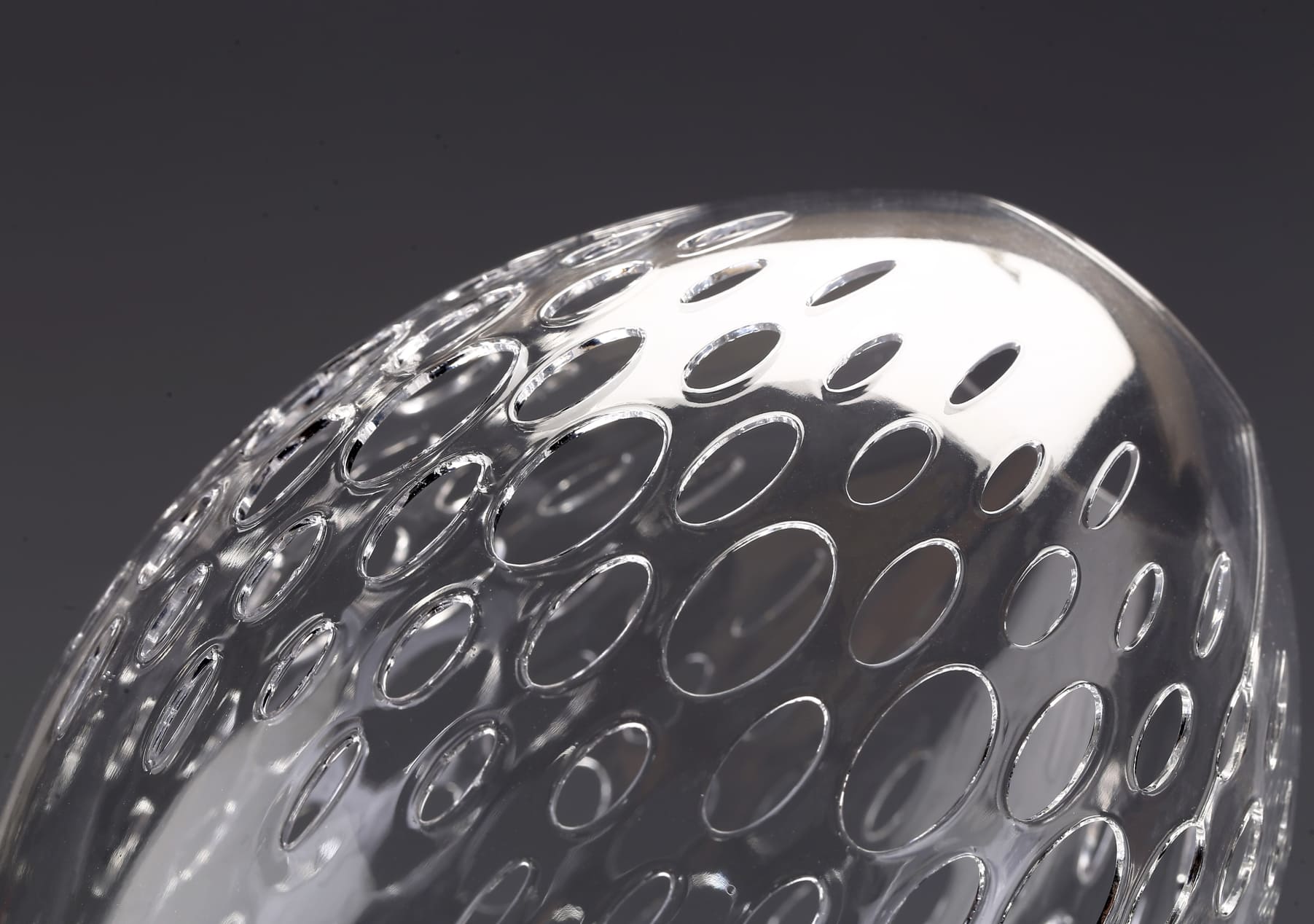

Image Copyright © 3DSPRO Limited. All rights reserved.

Step by Step Workflow

Post‑processing in LCD 3D printing follows a systematic workflow. Each stage contributes to the final quality of the part, and engineers must treat the process as a controlled sequence rather than a set of optional tasks.

1. Part Removal from the Build Plate

• Tools: Scraper, gloves, protective eyewear.

• Process: Detach the part carefully to avoid damaging delicate features. Engineers often use angled scrapers to minimize stress on thin walls.

• Considerations: Excessive force can deform the part. Heating the build plate slightly may ease removal.

2. Resin Cleaning

• Objective: Remove uncured resin from the surface.

• Methods:

1. Isopropyl Alcohol (IPA): Common solvent, effective but volatile.

2. Ethanol: Less aggressive, suitable for sensitive resins.

3. Specialized Cleaners: Formulated to reduce swelling and preserve detail.

• Techniques:

1. Manual rinsing in solvent baths.

2. Ultrasonic cleaning for complex geometries.

3. Agitation or rotating baskets for batch processing.

4. Engineering Trade‑offs: Longer exposure improves cleaning but risks swelling or cracking. Engineers must balance solvent concentration and time.

3. Support Removal

• Timing: Supports can be removed before or after curing.

• Pre‑curing removal: Easier cutting, less brittle.

• Post‑curing removal: Cleaner break, reduced smearing.

• Tools: Flush cutters, scalpels, or automated support removal systems.

• Considerations: Support placement during CAD design impacts ease of removal. Engineers optimize support geometry to minimize scarring.

4. UV Post‑Curing

• Objective: Complete polymerization and enhance mechanical properties.

• Equipment: UV curing chambers, handheld lamps, or rotating platforms.

• Parameters:

1. Wavelength: Typically 405 nm.

2. Duration: 5–30 minutes, depending on resin type and part thickness.

3. Rotation: Ensures uniform exposure.

• Engineering Impact:

1. Increased tensile strength and hardness.

2. Improved heat resistance.

3. Reduced creep under load.

• Risks: Over‑curing can cause brittleness or discoloration. Engineers must calibrate exposure protocols.

5. Surface Finishing

• Sanding and Polishing: Removes layer lines and support scars. Engineers use progressive grit levels for precision.

• Coating: Clear coats enhance durability; primers prepare surfaces for painting.

• Painting: Adds aesthetic value for consumer products or prototypes.

• Functional Treatments: Plasma cleaning or vapor smoothing for specialized applications.

• Outcome: A polished, professional finish that meets both mechanical and aesthetic standards.

6. Quality Assurance

• Inspection: Visual checks for residue, cracks, or warping.

• Dimensional Verification: Calipers or 3D scanning to confirm tolerances.

• Mechanical Testing: Tensile or compression tests for functional parts.

• Documentation: Engineers record post‑processing parameters for repeatability.

Engineering Considerations by Application

Different industries impose unique requirements on LCD 3D printing. Post‑processing must therefore be tailored to the application, balancing mechanical, aesthetic, and regulatory demands.

1. Dental and Medical Models

• Requirements: Biocompatibility, sterilization, and dimensional accuracy.

• Post‑Processing Focus:

1. Thorough cleaning to eliminate toxic residues.

2. Controlled UV curing for chemical stability.

3. Surface smoothing for patient comfort.

4. Engineering Challenge: Balancing mechanical strength with biocompatibility. Over‑curing may compromise safety, while under‑curing leaves residues.

2. Jewelry and Miniatures

• Requirements: Fine detail preservation, aesthetic perfection.

• Post‑Processing Focus:

1. Gentle cleaning to avoid damaging intricate features.

2. Precision sanding and polishing for flawless surfaces.

3. Painting or plating for the final presentation.

4. Engineering Challenge: Achieving cosmetic perfection without compromising delicate geometries.

3. Functional Prototypes

• Requirements: Mechanical load testing, dimensional tolerances.

• Post‑Processing Focus:

1. Rigorous curing to maximize strength.

2. Dimensional verification for assembly compatibility.

3. Surface finishing for usability.

4. Engineering Challenge: Ensuring prototypes behave like production parts under stress.

4. Batch Production

• Requirements: Workflow efficiency, repeatability, quality assurance.

• Post‑Processing Focus:

1. Automated cleaning and curing systems.

2. Standardized support removal protocols.

3. Batch finishing techniques.

4. Engineering Challenge: Scaling post‑processing without sacrificing quality. Engineers must design workflows that balance throughput with precision.

5. Consumer Products

• Requirements: Aesthetic appeal, durability, safety.

• Post‑Processing Focus:

1. Polishing and painting for visual impact.

2. Coating for durability.

3. Safety checks for chemical stability.

4. Engineering Challenge: Meeting consumer expectations for both appearance and performance.

6. Specialized Applications

• Examples: Robotics components, drone parts, prosthetics, food‑safe printing.

• Post‑Processing Focus:

1. Application‑specific treatments (e.g., sterilization for prosthetics, coatings for food safety).

2. Mechanical testing for load‑bearing parts.

3. Engineering Challenge: Adapting post‑processing protocols to niche requirements without compromising general standards.

COMMENTS

- Be the first to share your thoughts!