Choosing the right material class for a functional 3D printed part often matters more than choosing a specific printer brand. Thermoplastics (printed with FDM/FFF, SLS, MJF, etc.) and photopolymers (printed with SLA/DLP/MSLA) offer very different tradeoffs in strength, toughness, heat resistance, surface finish, dimensional accuracy, post-processing, and cost.

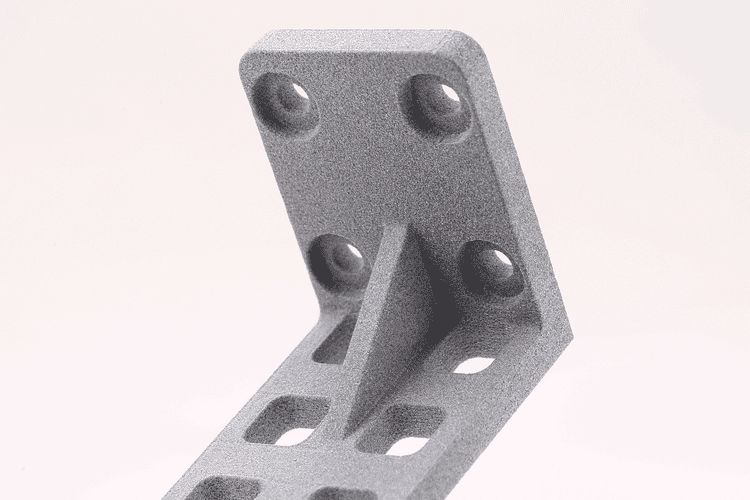

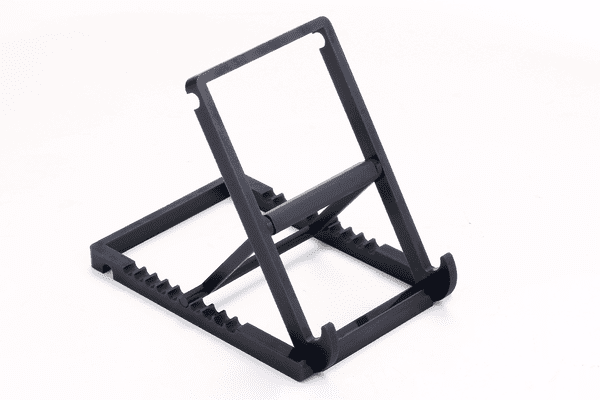

3D Printed Thermoplastics

Thermoplastics are polymers that melt and re-solidify with heat. In 3D printing the common techniques are fused filament and powder fusion processes. Typical thermoplastic chemistries used for functional parts include PLA and PETG (easy prototyping), ABS (general purpose), nylon (tough and wear resistant), PC (higher heat and stiffness), and specialty high-performance polymers like PEEK for extreme conditions.

Key Features

• Strength and Toughness: Many thermoplastics (especially Nylon, PC, PEEK) provide good tensile strength and impact resistance. Parts can be anisotropic with weaker interlayer bonds in layer-based FDM prints.

• Thermal Performance: Thermoplastics have a measurable heat deflection or glass transition temperature (HDT/Tg). Nylon and PC tolerate higher temperatures than PLA and PETG; PEEK is for very high temps.

• Chemical and Wear Resistance: Nylon shows good fatigue and wear resistance but can absorb moisture; PETG and PC offer better chemical resistance in many environments.

• Manufacturability: SLS and MJF produce near-isotropic parts with good mechanical properties; FDM parts are faster and cheaper for low volumes but exhibit layer adhesion concerns and visible layer lines.

• Post-processing: Thermoplastics can be annealed to reduce residual stresses and increase heat resistance (at the cost of some dimensional change), vapor-smoothed (ABS) for better surface finish, or machined for precision features.

• Practical Uses: Structural brackets, functional prototypes, jigs and fixtures, snap fits (when designed for the process), and low-volume end parts that require toughness and durability.

Image Copyright © 3DSPRO Limited. All rights reserved.

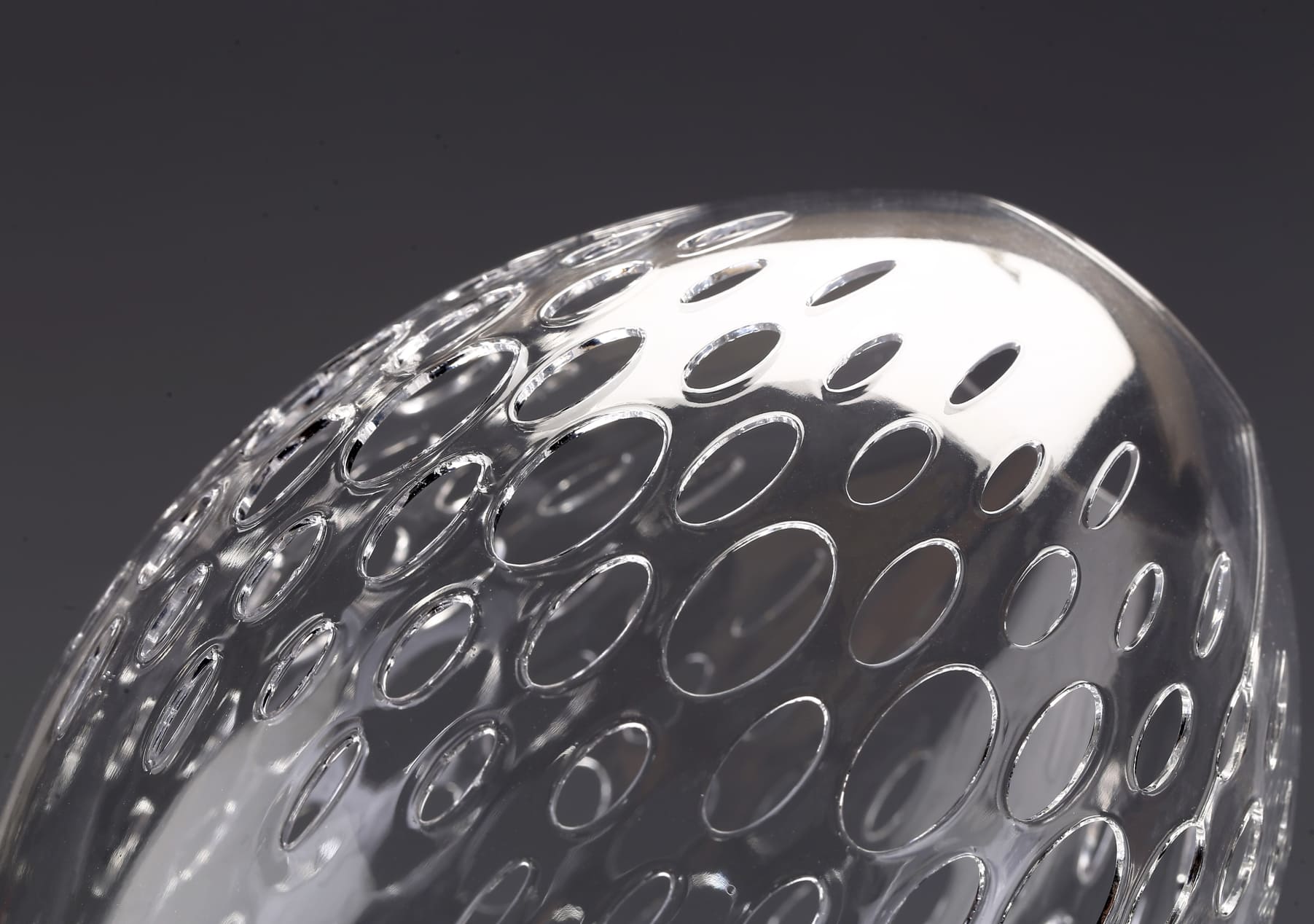

3D Printed Photopolymers

Photopolymers are liquid resins that cure into solids when exposed to light. Typical processes include SLA, DLP, and MSLA, layer curing methods that excel at high resolution and fine detail. Resin families range from general-purpose resins to engineering grades.

Key Features

• Surface Finish and Resolution: Photopolymer parts typically have far finer detail and smoother surfaces out of the printer than most thermoplastic prints.

• Mechanical Spectrum: Resins range from brittle (standard rigid resins) to surprisingly tough (tough or impact-resistant resins). However, even “tough” resins generally behave differently from thermoplastics under long-term load and fatigue.

• Thermal and Environmental Robustness: Standard resins are more sensitive to heat and UV, they can soften, creep, or yellow. High-temp resins exist but are costlier and have processing considerations.

• Post-processing: Critical steps, wash (remove uncured resin) and UV post-cure, determine final properties. Improper curing results in underperforming parts or dimensional drift.

• Biocompatibility and Precision: Resins can meet specialized certifications (e.g., dental, medical) and are ideal for optics, small housings, intricate geometries, and components where finish/fit matter.

• Practical Uses: Precision housings, optical mounts, dental/medical prototypes (with certified resins), fine-feature snap fits where geometry favors resin behavior, and small components requiring exceptional surface finish.

Image Copyright © 3DSPRO Limited. All rights reserved.

Process Constraints and How They Drive Material Choice

Material choice is inseparable from the print process. Here are some key constraints of thermoplastics and photopolymers

• Anisotropy and Orientation: FDM parts are directionally weaker across layers. Orienting stress-bearing features parallel to layer lines or choosing SLS/MJF (more isotropic) changes material selection. If a part must bear bending loads across layers, thermoplastic powder processes are preferable to FDM or brittle resins.

• Feature Resolution: If thin walls, micro-bosses, or fine threads matter, photopolymers usually win. Thermoplastics struggle with fine detail unless you use SLS or specialized small-nozzle FDM.

• Surface Finish and Tolerances: Resin prints typically require less finishing to reach tight aesthetics; thermoplastics often need sanding, smoothing, or machining.

• Build Volume and Throughput: Large parts and higher throughput favor thermoplastic extrusion or powder bed systems; resin systems can be efficient for many small high-detail parts (depending on printer and part packing).

• Post-process Labor: Resin workflows require chemical handling, washing, and curing; thermoplastics require thermal finishing, machining, or heat smoothing. Labor cost can sway the decision.

Technical Comparison

Tensile Strength and Modulus

Many engineering thermoplastics (Nylon, PC, PEEK) have higher toughness and tensile strength than standard resins. Engineering resins narrow the gap but still behave differently in fatigue.

Elongation at Break and Impact Resistance

Thermoplastic filaments like Nylon show higher elongation and energy absorption; standard resins can be brittle. Tough resins and flexible resins exist but often sacrifice stiffness or heat resistance.

Dimensional Stability

SLS/MJF thermoplastics offer good dimensional stability; FDM warping is a risk. Resins can be dimensionally stable after proper cure but may show long-term creep under load or change with UV exposure.

Heat Resistance (HDT/Tg)

Thermoplastics provide a clear range, PETG/PLA low, ABS/PC mid, PEEK high. Resins require special high-temp formulations to match thermoplastic heat resistance.

Chemical Resistance

Thermoplastics (e.g., PETG, PC) often resist common solvents and oils better than many resins; specialty resins exist for chemical exposure but must be selected carefully.

Surface Finish and Tolerances

Resins typically win for finish and fine tolerance; thermoplastics can be post-machined for tighter tolerances and structural needs.

Durability Comparison

Fatigue and Cyclic Loading

Thermoplastics like Nylon exhibit good fatigue performance if moisture content and orientation are controlled. Resins typically show poorer fatigue life unless formulated as “tough” engineering resins and validated under test conditions.

Creep Under Static Load

High-temperature thermoplastics (PC, PEEK) resist creep better than standard resins. Some high-temp resins approach thermoplastic creep performance but at higher cost and with strict post-cure needs.

Environmental Effects

UV light, humidity, and chemicals degrade many resins faster than thermoplastics. Nylon absorbs moisture, which affects mechanical properties, so conditioning and environmental testing are important.

Impact and Wear

For wearable, sliding, or load-absorbing parts, thermoplastics (especially filled nylons or engineering grades) are typically preferred. Resin parts can be suitable for light duty or when encapsulated/coated.

Cost Comparison

Material Cost

Basic resins and basic filaments are often comparable per print-volume, but engineering resins and high-performance thermoplastics (PEEK) are expensive.

Equipment and Per-Part Cost

FDM printers are cheaper upfront; SLS/MJF and high-end resin systems have higher capital and operational costs (printing services are good choices). Powder processes deliver better yield for complex, load-bearing parts at volume.

Post-process Labor and Consumables

Resin printing demands wash stations, alcohol, PPE, and time for cure, which add recurring costs. Thermoplastic post-process (sanding, annealing) also costs time but differs in consumable profile.

Yield and Scrap

Parts needing tight tolerances often require rework; brittle resins may see higher scrap in load tests. Powder processes may offer better yield for functional parts at the cost of higher machine time.

Outsourcing vs In-House

For small runs, service bureaus can be cost-effective, especially for SLS or high-end resins—because you avoid capital expense and learning-curve scrap.

Choose thermoplastics when you need toughness, fatigue resistance, higher heat tolerance, or long service life. They’re also better for parts that will be post-machined or endure mechanical abuse.

Choose photopolymers when resolution, surface finish, and fine detail matter more than long-term toughness, or when regulatory-grade resins are required (dental, medical prototypes).

For many projects, a hybrid approach, using resin for precision features and thermoplastic inserts for load-bearing sections, delivers the best balance.

COMMENTS

- Be the first to share your thoughts!