Whether you’re designing an outdoor bracket, a medical fixture, or a lightweight aerospace component, understanding how materials age and how the printing process and geometry accelerate or slow that aging determines whether a part survives or fails.

Fundamental Aging Mechanisms

Materials change over time via chemical and physical paths. Recognizing the dominant mechanisms helps you choose materials and test them realistically.

Chemical Degradation

Polymers commonly suffer chain scission (breaking of polymer chains) and oxidative attack. Oxygen and sunlight (UV) drive photo-oxidation at the surface, which produces brittle, discolored skin and reduces fatigue life. Hydrolysis, reaction with water, is critical for nylons and some esters (e.g., PET-based materials). Water molecules cleave polymer chains and change mechanical properties.

Physical Processes

Time and temperature drive glass transition shifts, crystallinity changes, and stress relaxation. Thermally-activated processes cause slow creep under sustained load; for polymers, creep at service temperature is often the limiting lifetime. Glass transition (Tg) drift, especially in amorphous resins, changes stiffness and can convert a tough material into an embrittled one.

Mechanical Fatigue and Interfacial Failure

Repeated loading creates microcracks that grow each cycle. In layer-based prints, layer interfaces and poor interlayer fusion are preferred crack-initiation sites. Fatigue life is often much shorter than static strength suggests.

Environmental Drivers

UV exposure, temperature cycling (freeze/thaw or hot/cold cycles), humidity, chemical exposure (solvents, fuels, salts), and biological agents (molds, microbes) all accelerate chemical and physical aging.

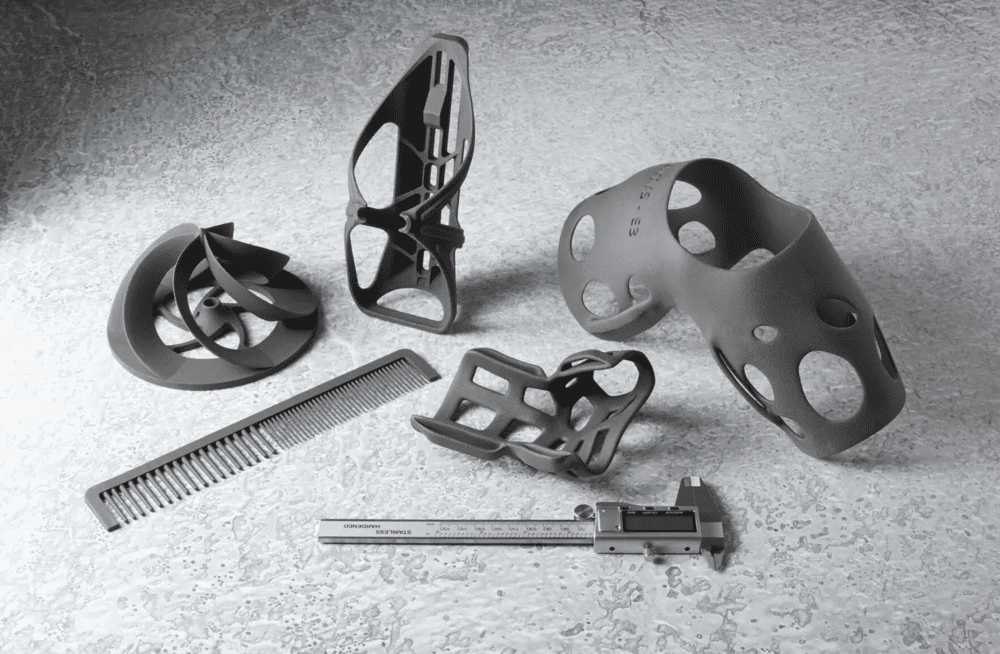

Image Source: Formlabs

How Process and Geometry Influence Aging

Layer Anisotropy and Adhesion

Layered processes produce anisotropic strength. Strength across layers (Z-direction) is typically lower than in-plane strength. That interlayer weakness concentrates stress and accelerates delamination, especially under cyclic loading or solvents that infiltrate layer gaps.

Porosity and Incomplete Fusion

Powder processes and filament extrusion can leave microvoids. Voids trap moisture and chemicals and reduce the effective cross-section area, shortening fatigue life. In metals, the lack of fusion defects are critical crack starter for high-cycle fatigue.

Surface Roughness and Stress Concentrators

Rough surfaces and sharp transitions concentrate stress and provide sites for environmental attack (UV exposure acts on surface peaks first). Small notches, holes, or thin walls increase local stresses and accelerate creep and crack growth.

Geometry-Driven Moisture and Contaminant Trapping

Internal cavities, lattice structures, and deep channels retain water and contaminants that promote hydrolysis or corrosion. Design features that allow drying or drainage reduce these risks.

Print Orientation and Process Settings

Orientation that aligns principal stress with stronger print directions, higher extrusion temperatures (when appropriate), slower speeds for better fusion, and reduced raster gaps all improve long-term behavior.

Material Families: Typical Long-Term Behaviors

Thermoplastics

• PLA is biodegradable and susceptible to hydrolysis and creep at modest temperatures, fine for indoor, low-load uses, but poor for long outdoor service.

• ABS resists creep better than PLA, but yellows and embrittles under UV unless stabilized; solvents can attack it.

• PETG offers good chemical resistance and toughness, moderate moisture sensitivity.

• Nylon (polyamides) offers excellent toughness and wear resistance, but absorbs moisture, which lowers stiffness and can cause dimensional changes. Drying and moisture control are essential.

• PEEK/PEI are high-performance; high Tg and chemical resistance give excellent long-term stability for demanding applications.

Photopolymer Resins

Uncured or under-cured resins continue to react over time; proper post-cure drives crosslinking and stabilizes properties. Many resins degrade, yellow, or embrittle with prolonged UV exposure; use UV-stable formulations or protective coatings for outdoor use.

Powder-Bed Polymers

These prints often produce isotropic in-plane properties, but part density and powder reuse affect porosity and mechanical consistency. Amorphous vs crystalline polymer behavior dictates sensitivity to temperature and chemicals.

Metals

Metal prints can show excellent long-term performance if defects and residual stresses are controlled. Corrosion (environmental embrittlement) and fatigue from microstructural heterogeneity are primary concerns. Post-processing (stress relief, HIP) significantly improves life.

Composites and Filled Materials

Fiber-filled prints improve stiffness and creep resistance but introduce a critical fiber-matrix interface that can degrade (moisture swelling of matrix, fiber corrosion) and reduce long-term load transfer.

Design and Material Selection For Longevity

Design for longevity starts with matching material properties to the operating environment.

Select for the Environment

For UV or outdoor exposure, use UV-stabilized polymers or protective coatings. For humid environments, avoid hygroscopic polymers (or specify drying and controlled storage). For chemical exposure, choose chemically resistant grades or surface treatments.

Design Geometry to Reduce Stress Concentration

Use fillets instead of sharp corners, smooth thickness transitions, generous radii at hole edges, and avoid thin webs in high-stress areas. Where possible, orient prints so principal stresses align with stronger print directions.

Increase Safety Factors and Design for Repair

For long-lived components, choose higher safety factors and design connections that allow localized replacement or repair rather than replacing the whole assembly.

Control Process to Reduce Defects

Tighten tolerances on process parameters (temperature, speed, powder bed density), minimize voids through appropriate infill or densification, and pick orientations that enhance interlayer bonding.

Plan for Dimensional Change

Account for moisture uptake (nylon) and post-processing shrinkage (annealing/cure) in the initial design.

Post-Processing and Protective Strategies

Thermal Treatments

Annealing crystalline thermoplastics increases crystallinity and reduces internal stress, improving creep resistance and dimensional stability. Metals benefit from stress-relief cycles and hot isostatic pressing to close internal defects.

Surface Sealing and Coatings

Conformal coatings, varnishes, or UV blockers protect polymer surfaces from photo-oxidation and chemicals. Impregnation reduces porosity and moisture ingress and improves fatigue life for porous prints.

Chemical and Mechanical Finishing

Smoothing reduces surface roughness and removes micro-notches that initiate cracks. For photopolymers, complete post-cure under controlled heat and UV eliminates undercured regions.

Corrosion Protection for Metals

Passivation, plating, or protective paints mitigate environmental corrosion. Choose coatings compatible with service conditions.

Quality Control and Testing

Implement targeted mechanical tests, environmental exposure tests, and NDT methods to validate longevity under expected service conditions.

COMMENTS

- Be the first to share your thoughts!